Written by Eirini Volikou*

On the same day, three people enter a book store looking to buy the book The secrets of the Internet. The book retails for €20 but the price is not indicated. The bookseller charges the first customer to walk in – a well-dressed man holding a leather briefcase and the new iPhone – €25 for the book. A while later a regular customer arrives. The bookseller knows that he is a student with poor finances and sells the book to him for €15. Finally, the third customer shows up; a woman who seems to be in a hurry to make the purchase. She ends up purchasing The secrets of the Internet at the price of €23. None of the customers is aware that each one paid a different price because the bookseller used information he deduced from their “profiles” to deduce their buying power or willingness.

In our capacity as consumers, how would we describe such a practice?

Is it fair or unfair, correct or wrong, lawful or unlawful?

And how would we react were we made aware that it targets us as well?

The above scenario may be completely fictitious but could it materialize in the real world?

In principle, the conditions in “regular” commerce are not such as to allow the materialization of our scenario. The obligation to clearly indicate the prices of products in brick and mortar stores directly and dramatically limits the traders’ freedom in charging prices higher than those indicated based on each individual client. In e-commerce, though, reality can prove to be strikingly similar to our fictitious scenario.

The e-commerce reality aka the “bookseller” is alive

Not infrequently it is observed that the indicated price of a good or a service on e-commerce platforms is not the same for everyone but divergences occur depending on the profile of the future customer.

Our online profiles are composed of information such as gender, age, marital status, type and number of devices we use to connect to the internet, geographical location (country or even neighborhood), nationality, preferences and consumer habits (history of searches or purchases) and so on.

This information is made known to the websites we visit via cookies, our IP address, and our user log-in information and can be used not only to show results and advertisements relevant to us but also to draw conclusions about our purchasing power or willingness. In other words, the role of the fictitious bookseller play algorithms that use our profiles for the purpose of categorizing us and automatically calculating and presenting to us a final price that we would be prepared to pay for the subject of our search.

This price may differ between users or categories of users who are often unaware of such categorisation or of the price they would be asked to pay had the platform had no access to their personal data.

This practice is often referred to as personalised pricing or price discrimination.

It is not to be confused with dynamic pricing in which the price is adjusted based on criteria that are not relevant to any individual customer but based on criteria relevant to the market, such as supply and demand.

The issue of personalized pricing surfaced in the public debate in the early 2000s when regular Amazon users noticed that by deleting or blocking the relevant cookies from their devices – which meant being regarded as new users by the platform – they could purchase DVDs at lower prices. The widespread use of e-commerce in combination with the rampant collection and processing of our personal data online (profiling, data scraping, Big Data) has since paved the way for the facilitation and spread of personalized pricing.

The experiment aka the “bookseller” in action

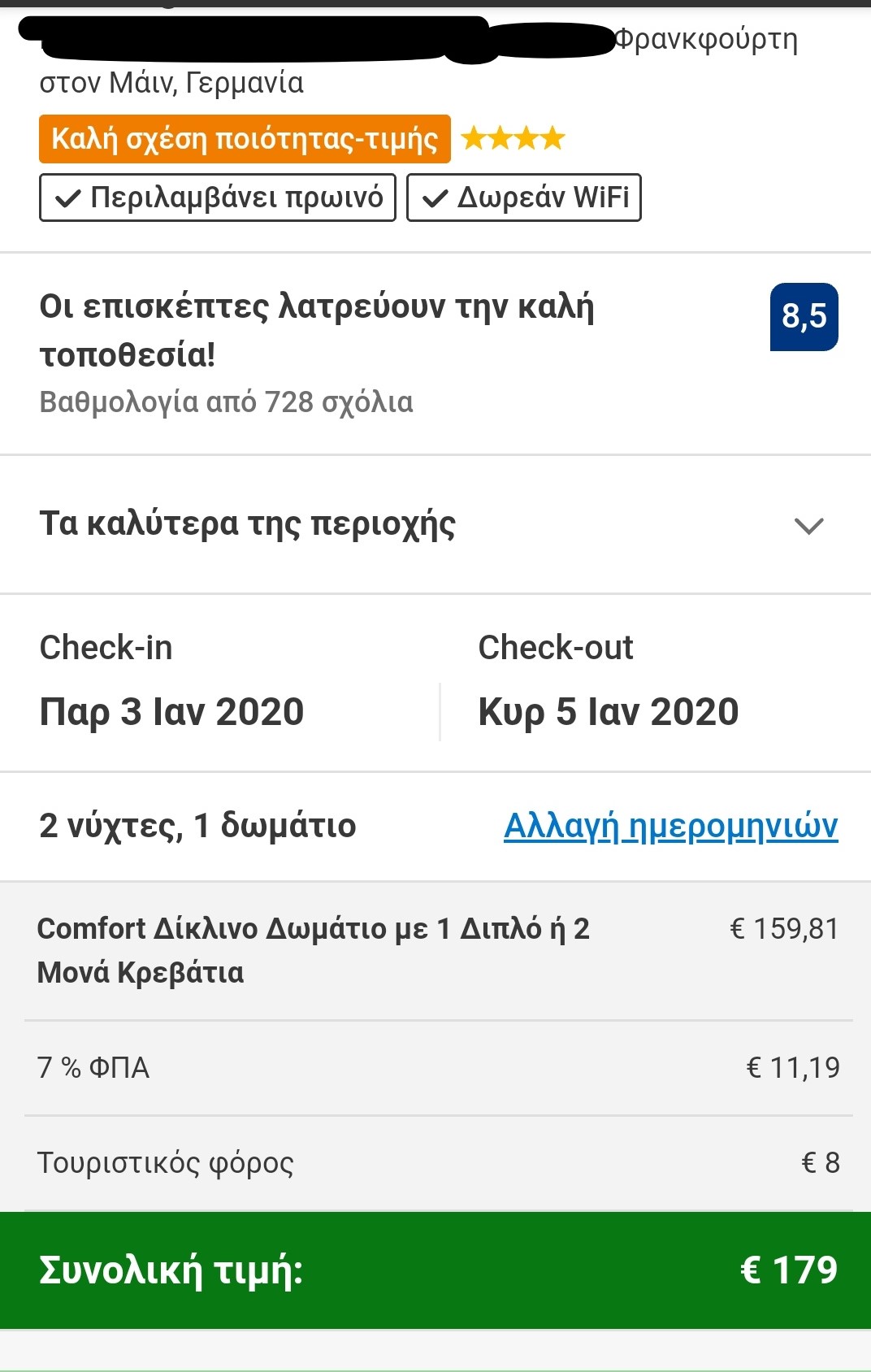

To put the practice to the test, consecutive searches and price comparisons were conducted on the same day (17/12/2019) for exactly the same room type (a “comfort” double room with one double or two twin beds) with breakfast for 2 travelers at the same hotel in Frankfurt, Germany on 3-5 January 2020. The searches were conducted on two different hotel booking websites and in all instances they reflect the lowest, non-refundable price option. The results are shown below:

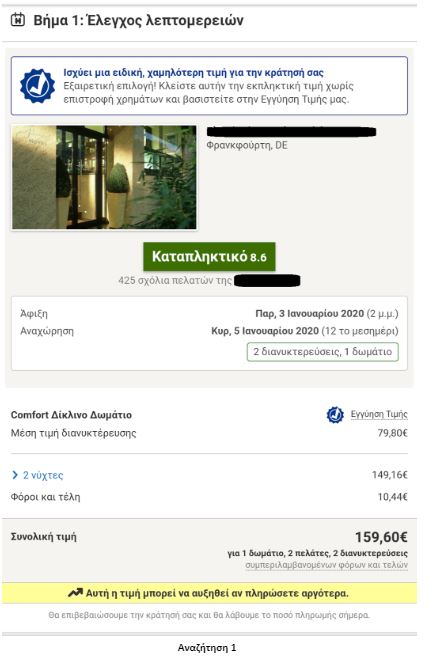

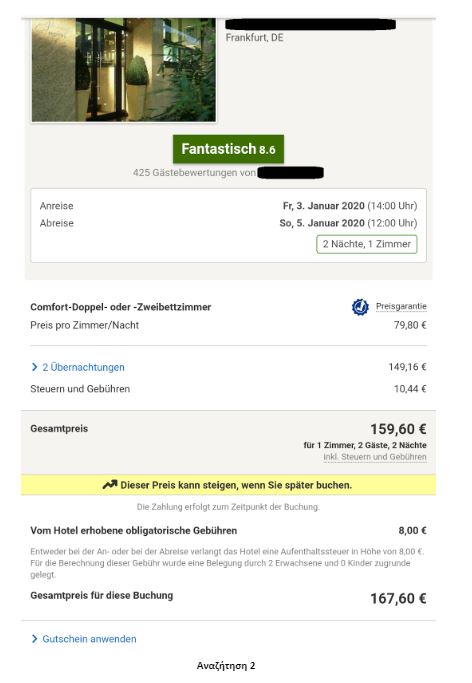

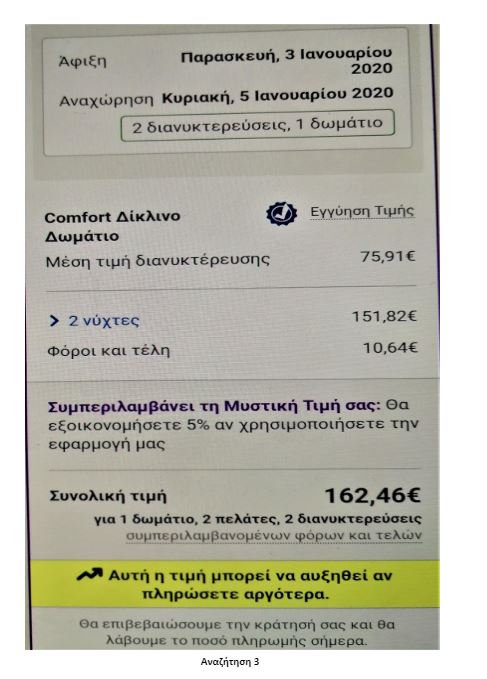

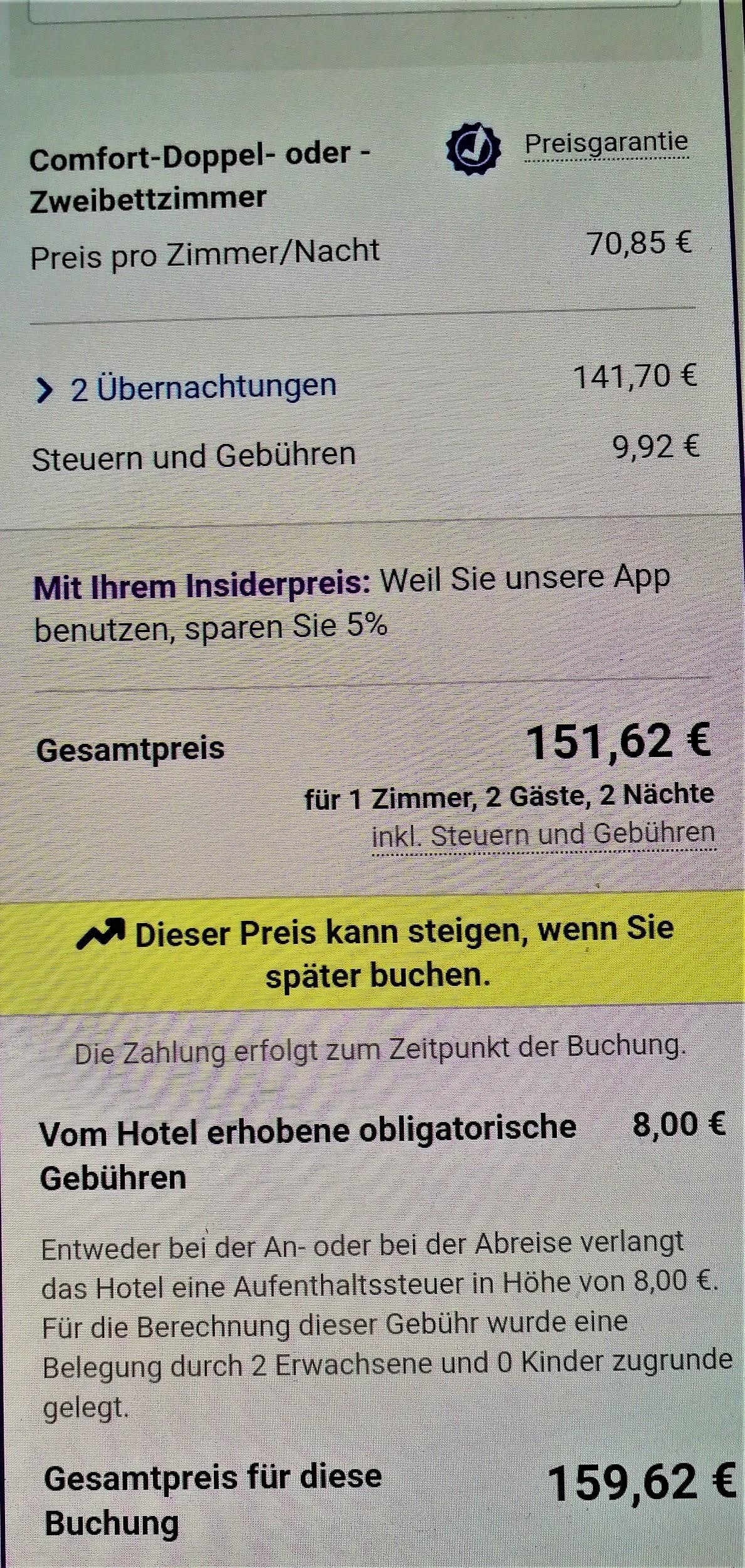

Website Α

| Device | Browsing method | Website version | Price in € | |

| 1 | Τablet | Browser | Greek | 159,60 |

| 2 | Tablet | Browser | German | 167,60 |

| 3 | Tablet | Application | Greek | 162,46 |

| 4 | Tablet | Application | German | 159,62 |

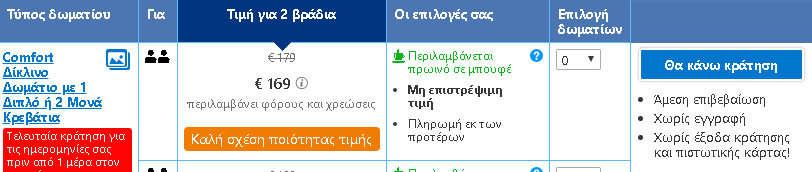

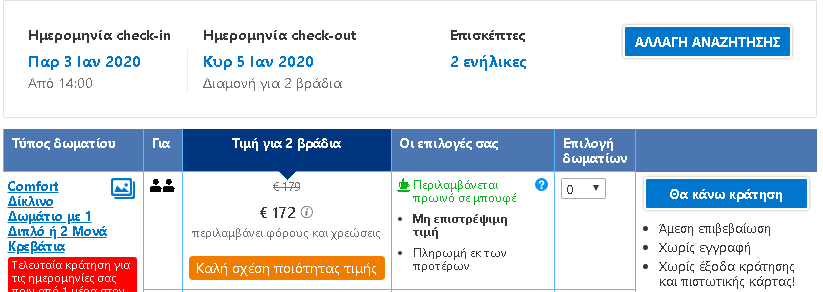

Website Β

| Device | Browsing method | Website version | Price in € | |

| 5 | Laptop | Browser | Greek | 169,00 |

| 6 | Laptop | Incognito browser | Greek | 172,00 |

| 7 | Smartphone | Browser | Greek | 179,00 |

Search 1

Search 2

Search 3

Search 4

Search 5

Search 6

Search 7

The search results show a range of different prices for the same room on the same dates.

There is a noteworthy price divergence depending on the consumer’s country or location. Even for the same country, though, the prices differ considerably depending on the type of device combined with the browsing method used.

All this information – or even the lack thereof in the case of incognito browsing – appears to play a role in the final price calculation and, hence, in the customized pricing for the users.

How is personalized pricing dealt with?

Personalised pricing, arguably, brings advantages especially for consumers with low purchasing power who benefit from lower prices or discounts and can have access to products or services that they could otherwise not afford. However, consumer categorization and price differentiation give rise to concerns because they are processes mostly unknown to consumers and obscure as to the specific criteria they employ.

At the same time, the use of parameters like the ones that appeared to influence the price in the hotel room experiment, i.e. country/language, device, and browsing method, does not guarantee a classification of purchasing power that corresponds to reality. What is more, research has shown that consumers, when made aware of the application of personalized pricing, reject this practice by a majority as unfair or unacceptable. This is largely true also in the event that personalized pricing would benefit them if they were also made aware that such benefit requires the collection of their data and the monitoring of their online or offline behavior.

When it comes to the legal approach to personalised pricing, different fields of law are concerned by it.

In the framework of data protection law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) does not explicitly regulate personalized pricing. Nevertheless, it provides that should an undertaking be using personal data (including IP address, location, the cookies stored in a device, etc.) it is obliged to inform about the purposes for which they are being used.

It follows that, if consumer profiles are being used for the calculation of the final price of a good or service, this should, at the very least, be mentioned in the privacy policy of the e-commerce platform.

The GDPR also requires consumer consent if personalized pricing has been based on sensitive personal data or if personal data is used in automated decision-making concerning the consumer.

From a consumer protection law perspective, traders can, in principle, set the prices for their goods or services freely insofar as they duly inform consumers about these prices or the manner in which they have been calculated. Personalized pricing could be prohibited if applied in combination with unfair commercial practices provided for in the text of the relevant Directive 2005/29/EC.

However, recently adopted Directive (EU) 2019/2161, which aims to achieve the better enforcement and modernization of Union consumer protection rules, will hopefully contribute to limiting consumer uncertainty and improving their position.

With the amendments that this Directive brings about not only is personalized pricing recognized as a practice but also the obligation is established to inform consumers when the price to be paid has been personalized on the basis of automated decision-making so they can take the potential risks into consideration in their purchasing decision (Recital 45 and Article 4(4) of the Directive). The Directive was published in the Official Journal of the EU on 18/12/2019 and the Member States should apply the measures transposing it by 28/5/2022.

It should be noted, albeit, in brief, that personalized pricing is an issue that competition law is also concerned with and, in particular, the possibility of charging higher prices to specific consumer categories for reasons not related to costs or for utilities by firms that hold a dominant position in a market.

In any case, staying protected online is also a personal matter.

At the Roadmap to Safe Navigation (in Greek) issued by Homo Digitalis, there can be found the behaviors we can adopt to protect our personal data while navigating through the Internet.

Consumers can adopt behaviors that help protect their personal data while browsing, such as using a virtual private network (VPN), opting for browsers and search engines that do not track users and using email and chat services that offer end-to-end encryption. To deal with personalized pricing, in particular, thorough market research, price comparison on different websites, or even different language versions of a single website, trying different browsing methods and, if possible, different devices can be a good start. It is important for e-commerce users to stay informed and alert in order to avoid having their profile used as a tool towards charging higher prices.

*Eirini Volikou, LL.M is a lawyer specializing in European and European Competition Law. She has extensive experience in the legal training of professionals on Competition Law, having worked as Deputy Head of the Business Law Section at the Academy of European Law (ERA) in Germany and, currently, as Course Co-ordinator with Jurisnova Association of the NOVA Law School in Lisbon.

SOURCES

1) European Commission – Consumer market study on online market segmentation through personalized pricing/offers in the European Union (2018)

2) Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules

3) Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market and amending Council Directive 84/450/EEC, Directives 97/7/EC, 98/27/EC and 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council (‘Unfair Commercial Practices Directive’)

4) Commission Staff Working Document – Guidance on the implementation/application of Directive 2005/29/EC on unfair commercial practices [SWD(2016) 163 final]

5) Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)

6) Poort, J. & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2019). Does everyone have a price? Understanding people’s attitude towards online and offline price discrimination. Internet Policy Review, 8(1)

7) OECD, ‘Personalised Pricing in the Digital Era’, Background Note by the Secretariat for the joint meeting between the OECD Competition Committee and the Committee on Consumer Policy on 28 November 2018 [DAF/COMP(2018)13]

8) BEUC, ‘Personalised Pricing in the Digital Era’, Note for the joint meeting between the OECD Competition Committee and the Committee on Consumer Policy on 28 November 2018 [DAF/COMP/WD(2018)129]9) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/914691.stm